When COVID-19 hit the United States, small towns near ski areas such as Park City, Utah, and Sun Valley, Idaho, experienced some of the highest per capita cases; people from around the world had brought the virus along with their skis. As the coronavirus spread, gateway communities—communities near scenic public lands, national parks, and other outdoor recreational amenities—felt acute economic pressure as the virus forced them to shut down tourist activities.

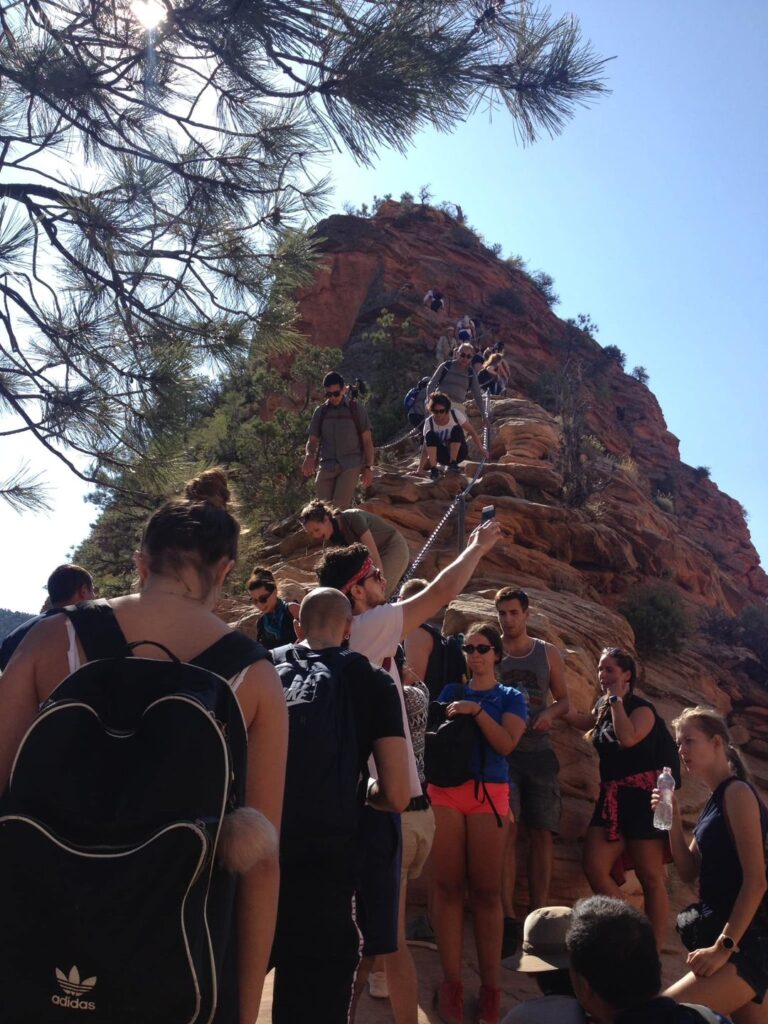

PHOTO CREDIT: National Park Service

Now, many gateway communities are facing an entirely new problem: a flood of remote workers fleeing big cities to ride out the pandemic, perhaps permanently. Like oil discovery led to western boomtowns, the pandemic has led to the rise of “Zoom Towns”—and with this so-called amenity migration comes a variety of challenges.

“This trend was already happening, but amenity migration into these communities has been expedited and it can have destructive consequences if not planned for and managed. Many of these places are, as some people say, at risk of being loved to death,” said Danya Rumore, director of the Environmental Dispute Resolution Program and research assistant professor in the Department of City & Metropolitan Planning at the University of Utah.

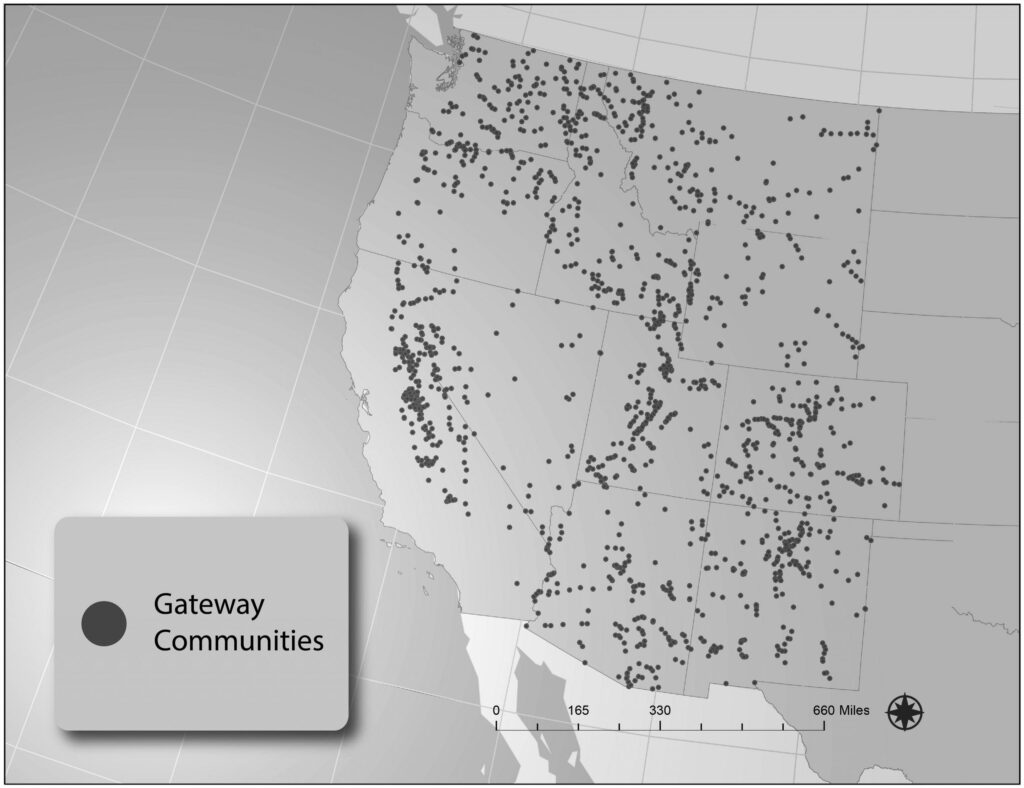

Rumore, who is from the gateway community of Sandpoint, Idaho, leads a team of researchers at University of Utah and University of Arizona who study planning and development challenges in western gateway communities. In a new paper in the Journal of the American Planning Association, the team published the results of a 2018 study involving a survey with public officials in more than 1200 western gateway communities and in-depth interviews with officials from 25 communities. In an eerie foreshadowing, a town manager from a developed gateway community said, “We don’t have the staff capacity to deal with major crises.”

“Our research shows that as small, rural gateway communities grow, they tend to experience a suite of big city problems, like housing affordability and transportation issues,” Rumore said. “In 2018 these public officials expressed a sense of already being behind the curve, and in need of additional capacity and resources to plan and adapt to rapid growth.”

In an effort to help gateway communities and the regions around them plan for and respond to COVID-19 and planning pressures, Rumore and others have launched the Gateway and Natural Amenity Region (GNAR) Initiative based at Utah State University in the Institute of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism. The GNAR Initiative will begin hosting a webinar series on amenity migration beginning Oct. 15.

Loved to death

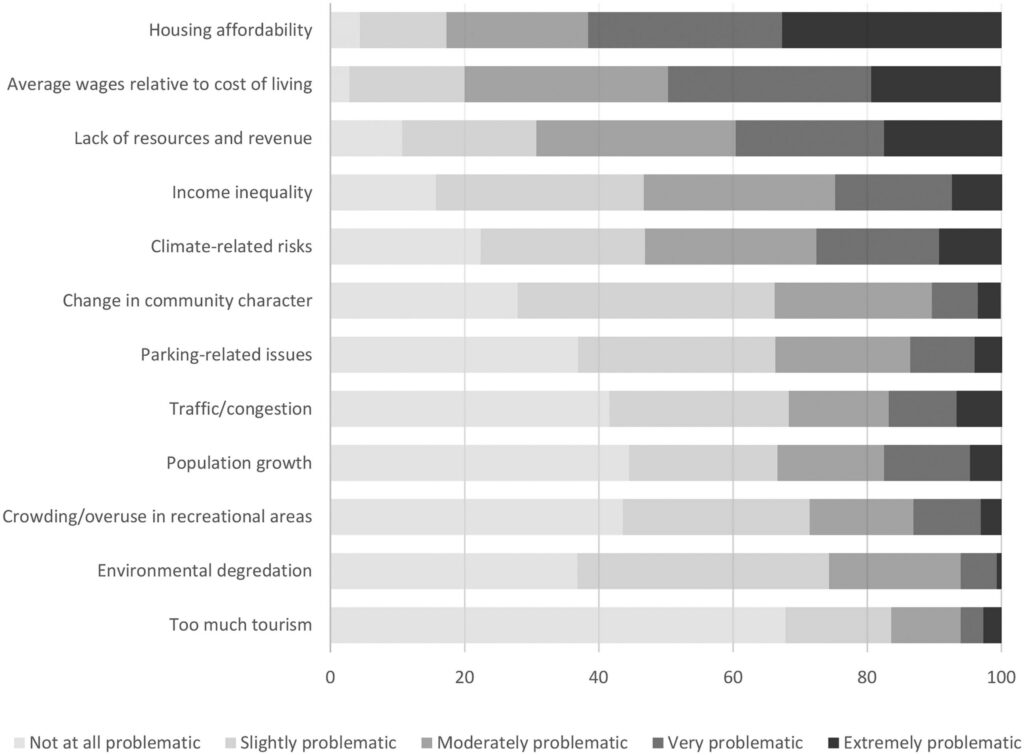

As part of the study, officials were asked specific questions about their communities’ planning challenges and opportunities. Housing and cost of living were key concerns for many gateway communities; 80% of respondents reported that housing affordability was moderately or extremely problematic for their community. Respondents also cited traffic congestion and other transportation issues as problems. These issues appear to be more strongly associated with population growth than with tourism and will likely get worse as COVID-19 drives rapid migration to these places.

The influx of remote workers could present economic development opportunities for gateway communities, Rumore said, but could also drive up housing prices and cost of living. Half of the survey respondents said that the average wage relative to cost-of-living was moderately or extremely problematic for their community in 2018, prior to this new wave of amenity migration.

“If you’ve been living there and growing up in this community and you don’t have a job that’s paying the salary of someone who’s in, for example, downtown Seattle, you’re going to be excluded from this community and your ability to invest in land and property if you haven’t already,” said Philip Stoker, assistant professor at the University of Arizona and co-author of the study.

The severity of challenges reported in the 2018 survey of public officials from more than 1,500 gateway communities.

For Zacharia Levine, doctoral student at the U and co-author of the paper, the topic is personal. For six years he served as the community and economic community director for Grand County, Utah, which encompasses the gateway city of Moab, the Colorado River, and two national parks—Arches and Canyonlands. Over the last 10 years, Moab visitation has grown to more than 3 million people per year. The locals felt it.

“The primary challenges residents reported included downtown congestion, housing affordability and availability, environmental degradation, and a general decline in quality of life. Much of Moab’s infrastructure was built when the town became a uranium boomtown; it was never designed to accommodate the world. Just in the last few years, we’ve had to build new water storage facilities, sewer treatment facilities, roads, and other public infrastructure,” said Levine. “Further, our local governments have struggled to increase their human resource capacities to plan for the future, let alone to deal with current issues.”

Levine began working with Rumore in hopes of finding guidance to address these immense challenges, but the academic planning literature lacked resources that focused on planning for these unique rural communities. The problem was hardly unique to Moab—some places such as Jackson, Wyoming, and Breckenridge, Colorado, have been experiencing amenity migration and related growth and development pressures for decades. Other gateway communities, such as Torrey, Utah that never thought it would happen to them, are just starting to feel the pressure. Like Rumore, Levine is worried that the flood of remote workers would catch many gateway communities, particularly those that are less developed, off guard.

“Many places have experienced this common trajectory. How does a gateway community navigate tourism, and growth writ-large, more gracefully?” Levine asked. “COVID-19 really blew the lid off that challenge.”

STAT PHOTO CREDIT: Stoker et. al. (2020) Journal of the American Planning Association

The GNAR Initiative

The GNAR Initiative is an affiliation of university faculty, government and state agencies, nonprofit organizations and community leaders that supports research, educational efforts, and capacity building to help public lands managers and others. The initiative provides an online toolkit for gateway communities, hosts educational events and community peer-to-peer learning forums, and supports cross-university research initiatives.

As part of its efforts to raise awareness about the likelihood of amenity migration to gateway communities and to share tools and resources, the GNAR Initiative will begin hosting a webinar series on amenity migration beginning Oct. 15.

“The main takeaway from our study and work with gateway communities is that these towns and cities need to plan ahead to manage change and the things that come with it,” Rumore said. “The goal of the GNAR Initiative is to help these places thrive and preserve the things that make them so special.”

The study was funded by the National Institute for Transportation and Communities. Lindsey Romaniello of University of Arizona also co-authored the study.